Introduction

Urban morphology, the study of the physical form of cities, is key to understanding how cities develop, evolve, and function. Every street, block, building, and open space contributes to the overall spatial pattern that defines the urban fabric. As cities worldwide face rapid urbanization, climate change, and the need for sustainable development, analyzing urban morphology provides critical insights for planners, architects, and policymakers.

This article explores the core concepts of urban morphology, historical developments, methods of analysis, and real-world applications. We will also look into how spatial patterns influence social interaction, transportation, and sustainability.

What Is Urban Morphology?

Urban morphology is the scientific study of the layout, form, and structure of urban areas. It considers how cities are physically arranged, how those arrangements came to be, and what they mean for contemporary and future urban living.

Key Elements of Urban Morphology

- Street Patterns – Grid, radial, linear, and organic street layouts.

- Plot Patterns – Arrangement and size of individual land plots.

- Building Forms – Shapes, heights, functions, and typologies of buildings.

- Public Spaces – Parks, plazas, and transitional spaces that shape city dynamics.

Historical Context of Urban Morphology

Ancient Cities

Early cities like Mesopotamian Ur or Ancient Rome had highly organized urban cores. Roman towns, for example, were based on a strict grid (the cardo and decumanus) reflecting military precision and administrative needs.

Medieval and Organic Growth

In contrast, many medieval towns grew organically, with narrow winding streets and irregular plots that responded to topography, trade routes, and social hierarchies.

Industrial Urbanism

The 19th century brought about rapid industrialization and new planning models. Cities expanded quickly, often with poor housing and minimal regulation. Morphologically, this created dense working-class neighborhoods and wider boulevards to accommodate new transport needs.

Modern and Postmodern Planning

The 20th century saw the rise of zoning, master planning, and architectural movements like Modernism that dramatically reshaped urban space—often favoring function over form. Later, Postmodern and New Urbanist approaches reemphasized traditional street patterns and mixed-use designs.

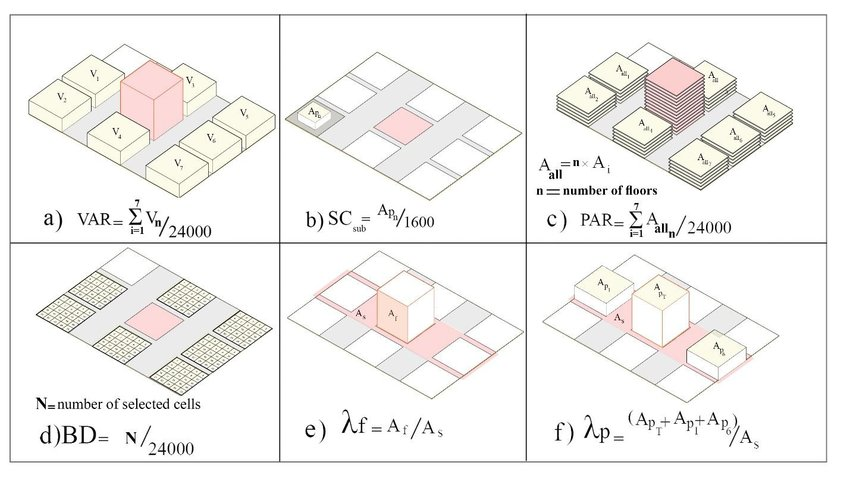

Methods of Urban Morphological Analysis

Urban morphology can be studied through various analytical lenses. Here are some major approaches:

Conzenian Approach

Developed by M.R.G. Conzen in the UK, this method focuses on the town plan, building fabric, and land use. It emphasizes the “burgage cycle” (a sequence of plot changes) to trace urban change over time.

Italian School (Muratori-Strappa)

This tradition focuses more on architectural typologies and the transformations of buildings. It links morphology closely with historical and cultural contexts.

Spatial Syntax

Developed by Bill Hillier and colleagues, spatial syntax analyzes connectivity and accessibility in urban networks using graph theory. It measures how street layouts affect movement patterns and social behavior.

Spatial Patterns in Urban Morphology

Spatial patterns determine how people navigate, inhabit, and perceive urban spaces. These patterns influence the social and economic functions of cities.

Grid Systems

- Pros: High connectivity, ease of navigation, and flexible land division.

- Cons: Can become monotonous and fail to respond to topography or climate.

Radial and Ring Patterns

Common in cities like Paris and Moscow, these create hierarchical centers and promote landmark orientation. However, they often cause congestion in central nodes.

Organic Patterns

Seen in cities like Fez or older European towns, these patterns result from centuries of incremental growth. They tend to promote walkability and cultural richness but are harder to adapt to modern infrastructure.

Hybrid Patterns

Most modern cities are hybrids, combining multiple systems. For example, Tokyo blends grid and organic forms, responding to both historical and modern influences.

Urban Morphology and Social Behavior

Walkability and Human Scale

Compact, mixed-use areas with well-connected street networks promote walkability, increase social interaction, and reduce car dependence.

Identity and Place-Making

Distinct urban forms foster strong local identities. Historic cores with preserved street patterns often enhance community pride and attract tourism.

Segregation and Inequality

Morphological patterns can reinforce social inequality. Gated communities, disconnected housing estates, and mono-functional zones reduce accessibility and social cohesion.

Urban Morphology and Sustainability

Urban form plays a central role in sustainability:

Land Use Efficiency

Dense, compact forms reduce land consumption and protect green spaces.

Transportation Energy

Well-connected street grids enable public transport and active mobility, reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate Adaptation

Morphology affects microclimates. Narrow streets and building orientation can either increase or mitigate urban heat islands.

Case Studies in Urban Morphology

Barcelona: The Cerdà Grid

Barcelona’s Eixample district is a textbook example of morphological innovation. Designed by Ildefons Cerdà in the 19th century, the grid system with chamfered corners improves airflow, mobility, and sunlight access.

Venice: Organic Urbanism

Venice demonstrates how water-based infrastructure and historical layering create a unique, human-scaled morphology. Its winding canals, narrow alleys, and piazzas create a timeless urban experience.

Brasília: Modernist Experiment

Designed by Oscar Niemeyer and Lúcio Costa, Brasília embodies modernist planning ideals—strict zoning and monumental geometry. While iconic, it faces criticism for being car-dependent and socially disconnected.

The Role of Technology in Morphological Studies

Modern technologies have revolutionized the study of urban morphology:

GIS and Remote Sensing

Geographic Information Systems allow precise mapping and spatial analysis, useful for measuring density, land use, and growth patterns.

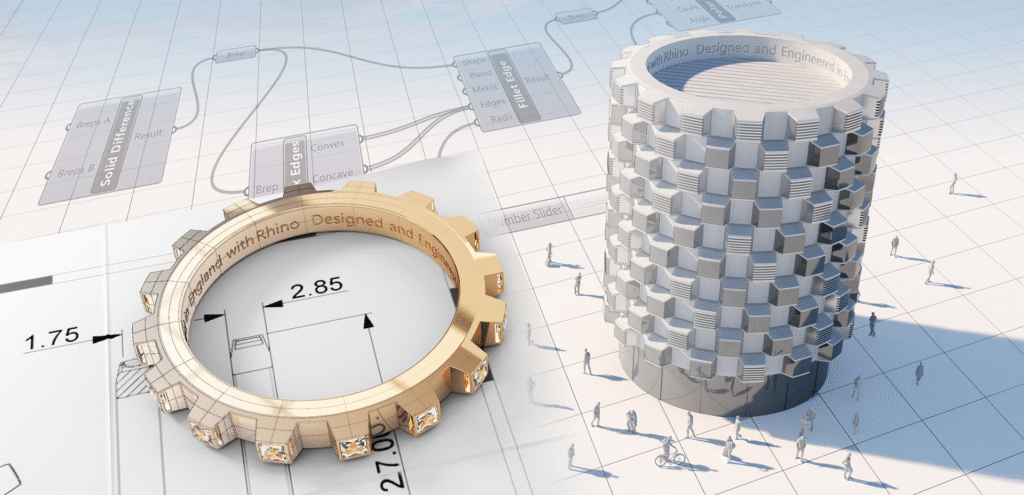

3D Modeling

Tools like Rhino or SketchUp help visualize urban forms and test design interventions at various scales.

AI and Big Data

Machine learning models can detect morphological patterns, predict urban growth, and support data-driven urban planning.

Also Read : Smart Cities, Smart Buildings: The Role Of Architecture In Innovation

Conclusion

Urban morphology is more than a technical study of city forms—it is a lens through which we understand human history, social interaction, environmental impact, and future urban challenges. As cities face unprecedented changes, from climate adaptation to digital transformation, understanding their physical structure becomes increasingly important.

By decoding the fabric of cities, we can design more inclusive, resilient, and livable urban environments that reflect both cultural heritage and future needs.

FAQs

1. Why is urban morphology important for urban planning?

Urban morphology helps planners understand how existing forms influence behavior, accessibility, sustainability, and historical continuity. It provides a foundation for making informed decisions about zoning, transport, and land use.

2. What tools are used to study urban morphology?

Common tools include GIS, remote sensing, spatial syntax software (like Depthmap), and 3D modeling platforms. Historical maps and on-site surveys are also vital.

3. How does morphology influence social behavior?

Urban form shapes how people interact, move, and build communities. For instance, walkable neighborhoods with mixed-use patterns encourage more social interaction and stronger local economies.

4. Can urban morphology help in climate adaptation?

Yes. Morphological analysis helps design cities with better ventilation, solar access, and water drainage—crucial for mitigating urban heat islands and managing extreme weather.